Workers across Broadway, Off-Broadway, and Regional theatre are represented by various unions, covering everyone from the front-of-house staff, designers, stagehands, and actors to the director. These unions work to maintain equitable pay, safety and protections, and benefits for their membership through collective bargaining agreements with the producers and owners of theaters.

For newcomers to the industry, learning and understanding the jurisdictions and roles of each union can be a daunting task. But if you want to work on Broadway, becoming a part of a union is not only encouraged, it's often a requirement. For this reason, it's essential to have at least a baseline understanding of our different unions, not only when it comes time to consider joining but also in understanding your peers and co-workers' roles as well.

Below is a brief overview of the unions representing stagehands, designers and crew. The details of their jurisdictions and contracts are beyond the scope of this post, but more information may be found on their linked websites.

The League(s)

Before diving into each union, it's worth knowing who represents the theaters and producers they negotiate with. These "Leagues" act as dealing collectives or trade associations. Each union may have a different set of contracts for each League.

The Broadway & Off-Broadway Leagues

Founded in 1930, The Broadway League, as the name suggests, comprises producers, owners, general managers, and suppliers on Broadway and related tours. Their membership includes all of the For-Profit theaters on Broadway, including the Shubert Organization, The Nederlanders, Jujamcyn, and ATG.

The Off-Broadway League, in turn, represents 26 companies and theaters composing Off-Broadway. They were founded in 1959.

The League of Resident Theaters

More commonly referred to as LORT, it is the most prominent associate of theaters in the United States. Originally composed of 26 theaters at its 1966 founding, they now comprise 75 Regional theaters across 29 States and D.C. This membership also includes the 4 Not-For-Profit Theater companies on Broadway: Lincoln Center, Second Stage, Manhattan Theater Club, and Roundabout. Theaters fall under a letter grade (A - D) to further distinguish their membership based on box office sales totals. A special designation of A+ is given to the non-profit Broadway houses.

I.A.T.S.E.

The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, (Deep Breath) Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States, Its Territories and Canada, better known as IATSE — or just "The IA" or “The International”— is the largest union representing theatrical workers.

The union was founded as the Theatrical Protective Union of New York (TPU) in 1886. By 1893, they were joined by stagehand unions in 10 other cities to found NATSE, the National Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees. They Became INTERnational when Canadian locals joined in 1902. Each town or location was given a specific number and allowed to govern itself as a "local" of the union.

The union has grown to include designers, wardrobe crew, makeup and hairstylists, press agents, managers, and ushers. Traditionally, the locals were designated by location, but today, it has expanded to also delineate types of work and contracts.

Local One

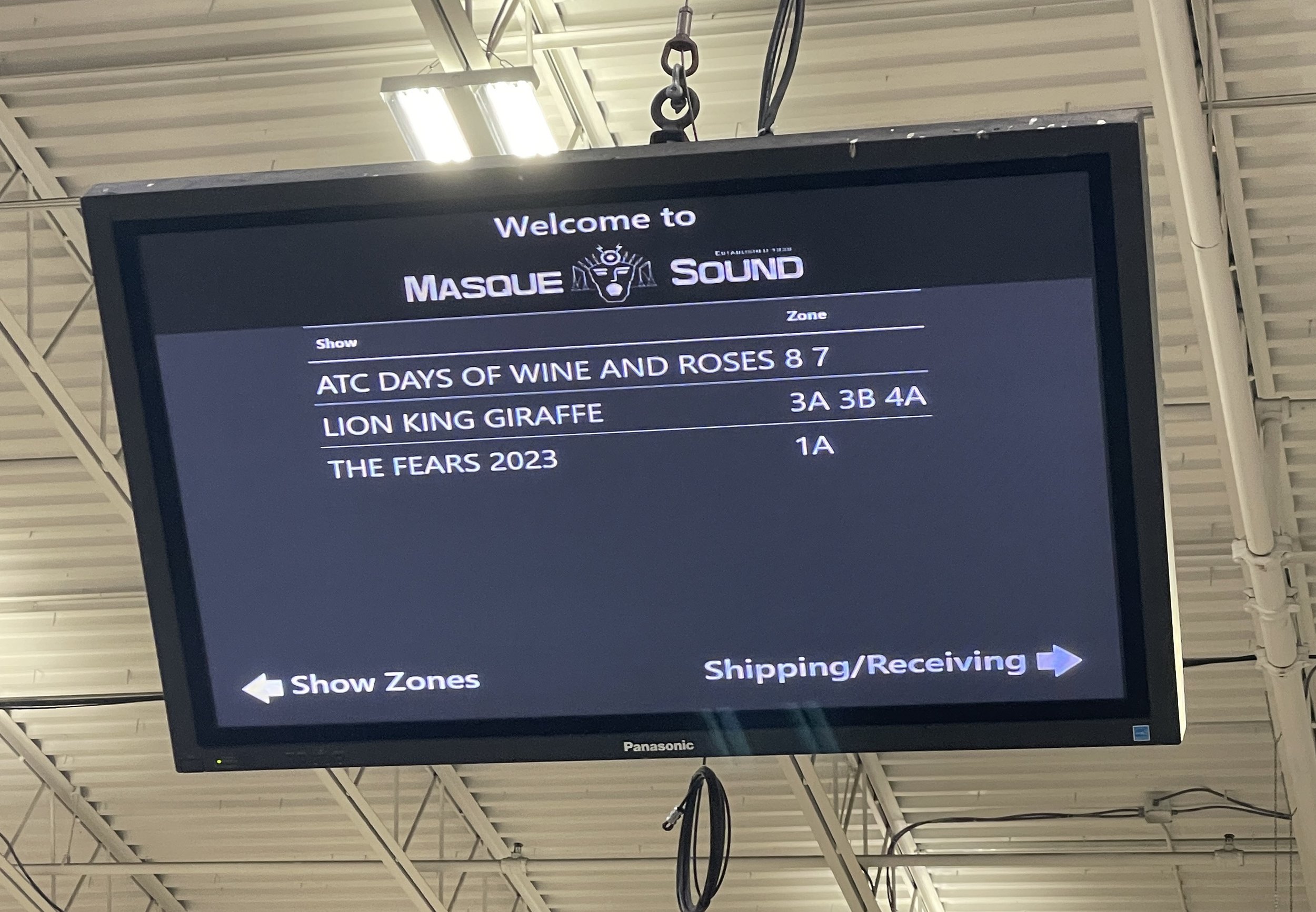

TPU of New York, the founding union behind IATSE, was designated Local One in honor of its contribution. Local One represents all Broadway stagehands, including electricians, sound engineers, carpenters, riggers, video engineers, and special F.X. The union is most prevalent on Broadway, making up the majority of house crew and staff in the theaters. For those looking for a long-term career as a Broadway stagehand, Local One should be on your list of unions to consider. As of this writing, the bounds of Local One are also expanding to Off-Broadway theaters as more and more workers seek unionization.

It's important to note that you do not have to be Local One to accept Local One work, and consecutive work under Local One contracts is a popular way to eventually join the union. You may also apply through apprenticeship or gain affiliation through workplace organization. More info here.

ACT and “Pink Contracts”

The Associated Crafts & Technicians arm of IATSE also plays an essential role for Broadway stagehands. ACT card members do not belong to any specific local but instead are covered under the international itself. This allows ACT members to work under a "Pink Contract" (traditionally printed on pink paper) Pink Contract workers can work in union houses and on national tours through different locals but rather than being hired by the house, they are employed by the production, and travel with it in the case of a tour. Importantly, any member of a stagecraft local, such as Local One, can work under a pink contract if called for, this is not exclusive to ACT but rather, ACT membership facilitates working under a pink contract for those who are not already a member of a home local.

On Broadway, a number of pinks are negotiated independently for every show to compliment the Local One house positions both in the tech process (known as “advance pinks”) and some run of show crew.

Getting an ACT card requires accepting a pink contract, at which point you join and pay into IATSE.

Local 764 and Local 798

The wardrobe crew on Broadway is represented by Local 764, whose jurisdiction covers all theatres within a 50-mile radius of Columbus Circle, NYC, and Long Island. In 2010, the local expanded to include child guardians across several Broadway theaters.

Local 798 represents Make-Up-Artists and Hair Stylists across 22 East Coast states and Broadway.

Both locals accept applications through their websites, Local 764 and Local 798.

USA Local 829

Despite being founded in 1897, The United Scenic Artists of America didn't find its permanent home in IATSE until 1999. USA Local 829 represents all concentrations of designers, their assistants/associates, and scenic artists. They have collective bargaining agreements with Broadway, Off-Broadway, and LORT theaters. Though it represents all designers nationwide, committees are divided into regions: Eastern, Central, Western, and National.

Joining the union can be done through the Annual Exam and Portfolio review process, The off-Broadway Membership Candidate process, or by professional membership application if you have worked on a USA contract but have yet to become a member. More info from USA829 and OBADAG.

Just getting started

As you can tell, the landscape of unions in the theatre can be pretty complicated. Directors, Choreographers, Actors, Writers, and more will be covered in Part 2.

Have more questions about unions? Write me at owenmeadowsdesign@gmail.com, or feel free to comment below.

Owen